COLIN DODD (England, b. 1954)

Dodd has an evidently inexhaustible supply of different manners of brushwork. The majority of these are employed for figuration with varying degrees of modelling, but the rest establish shifting abstract fields in which the artist masterfully assembles his plenitude of figurative imagery. A typical large painting by Dodd can contain as many as ten distinct stylistic modes of abstraction and figuration, skillfully unified by a visual logic that unfailingly persuades. Dodd's work richly acknowledges the historical fact, and the validity, of the progressive breakup of painting under Modernism and Post-Modernism. His paintings do this by frankly containing traces of that very disintegration. Yet at the same time, Dodd's individual art is violently opposed to, and convincingly transcends, this historically recent, complete disintegration of the art of painting. In the end, Dodd's work accomplishes its artistic—visual and intellectual—transcendence by means of its enormous, reconstitutive complexity in recovering innovatively the lost and abandoned, technical and expressive resources of painting.

The cultural comprehensiveness of Dodd's imagery is vast. His command of technique appears endless in its ingenuity, and is so ceaseless in its restless change from painting to painting, and within single paintings, as to give a capsule survey of painting styles for the past century and a half. His paintings erupt with imagery catalyzed into a poised and compelling harmony. They float multiple images in an intricate narrative assemblage, achieving an interwoven and balanced compositional mastery. The sheer intelligence behind his manipulation of varied styles and images, into a state of firm equilibrium, brings back into painting a level of intellectual application and complexity that it has been lacking for several decades, under the reign of the late-dismantlement esthetic of deconstructive Post-Modernism, which is now definitively finished. Among the small, international group of artists now working to reconstitute collectively the lost art of painting—from its complete, systematic dismantlement under Modernism and Post-Modernism—none demonstrates work of more visual intelligence and imagination than Dodd's.

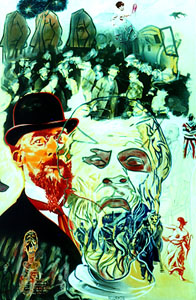

Erik Satie, Composer Oil on canvas 48.5"w x 72.75"h Colin Dodd

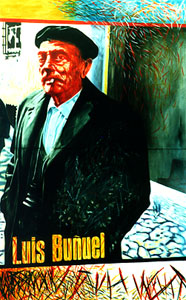

Luis Buñuel Oil on canvas 48"w x 76"h Colin Dodd

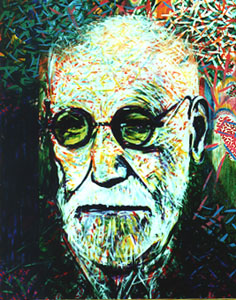

Sigmund Freud Oil on canvas 48.25"w x 60.75"h Colin Dodd

Portrait of Sergei Eisenstein

Colin Dodd

England, b. 1954

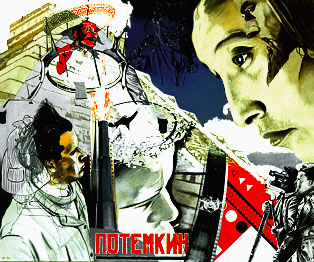

Colin Dodd demonstrates a single-handed, single-minded ability to effectively resuscitate the long-dead art of portraiture. His picture of Eisenstein (1898-1948) is filled with images of the Russian film director's life and work. All the images are juxtaposed or superimposed to yield a masterfully integrated work, composed of many distinct parts.

The Mayan pyramid rising into the upper left corner of the painting is counterbalanced on the right by the large profile of a Mayan woman looking down toward the center of the painting. Both images derive from a scene in Eisenstein's film Thunder over Mexico (1933). So do the dark blue sky and the outline of a skull wearing a mustache and sombrero, the latter image taken from an annual Mexican folk festival, the Day of the Dead. The skull is filled in with a red portrait of Josef Stalin. The profile of Ivan the Terrible in the upper right corner is from Eisenstein's historical film (1944) about this 16th-century ruler, the first Czar of Russia.

A faint, lavender, pointed shape, rising on the left side of the picture, represents the forward deck of the battleship Potemkin, whose crew's mutiny in 1905 against their pre-revolutionary, Czarist officers is the focus of another Eisenstein film (1925). The Russian spelling of Potemkin, this film's title, appears at the bottom of the painting in red. The two circular shapes on the ship's deck are meant to suggest the spectacles of the ship's surgeon, eyeglasses used in the film to magnify the maggots in meat fed to the outraged, rebellious crew. The fire exploding from the ship's cannon in the picture, overlaid on a film strip, is ironically directed at the portrait of Stalin. The frozen image of a screaming woman, on another film strip to the right, is that of a nurse in the same movie, who sees a child shot in the famous massacre (also 1905) on the stone steps of the Ukrainian hillside port city of Odessa.

There are four images of Eisenstein himself in the picture: 1) lower left on the bridge of the Potemkin; 2) bottom center editing film; 3) bottom right directing his cameraman; and 4) drawn in outline in the sky above. The two drawings traced over the lower left portrait are from caricatures by Eisenstein, one portraying himself in an overcoat, and refer to his earlier career as a political cartoonist.

Portrait of Sergei Eisenstein Oil on canvas 62.75"w x 51.75"h Colin Dodd